Consolidation and the sector's coverage

by Giovanni Curatolo, Index and Research Analyst

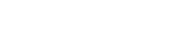

Since the pandemic, the listed real estate sector has been quite volatile: the post-covid rebound through 2021 and early 2022 ended when the main central banks in Europe took a hawkish stance, which pushed property companies to adapt to a “higher-for-longer” interest rate environment. This, combined with war outbreaks and geopolitical turmoil, has contributed to a slowdown in the growth of the sector, which has expanded by roughly 11% over the past five years in terms of cumulative market capitalization, trailing the estimated 46% growth of the broader European equity market[1]. Exhibit 1 shows the evolution of the European equity market and the % captured by LRE as of June 30, 2025.

Exhibit 1

Source: EPRA Research – TMT report

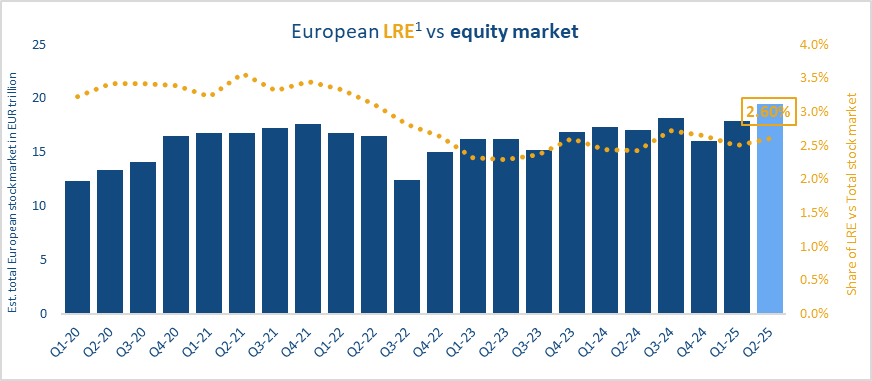

As a result of this, some property companies may lack visibility and struggle to attract a broader array of ‘generalist’ equity investors. This is evident when comparing the number of analysts covering listed real estate companies against other equity sectors (Exhibit 2)[2].

Exhibit 2

Source: EPRA Research - LSEG Data

On average, amongst European equity sectors, listed real estate falls within the bottom five sectors when it comes to analyst coverage; and although the STOXX 600 might not be representative enough due to its ”large” cap nature, it may provide insights into which sectors are most “overlooked” in terms of analyst’s coverage.

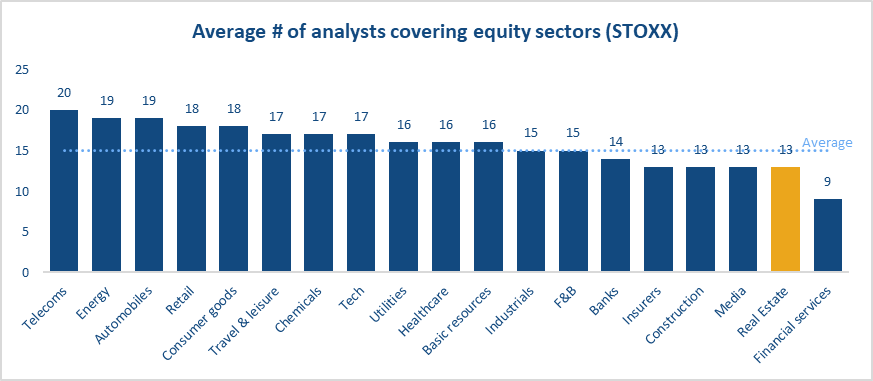

Within the universe of the FTSE EPRA Nareit Developed Europe Index (comprising of 105 companies of different sizes, regions, and sectors), REITs and property companies get almost half of the coverage than the average company in STOXX 600 (8 analysts against 15). Exhibit 3 illustrates the average number of analysts covering the FTSE EPRA Nareit Developed Europe Index constituents as of June 2025. Coverage of large constituents is on par with that of the listed real estate names included in the STOXX 600 (13), whereas constituents at the lower end of the index (38 out of 104) receive, on average, less than a quarter of the analyst coverage of those at the higher end[3]. One reason for this is that, due to the limited free-float market capitalization (EUR 1 billion or less), smaller companies may not always meet large fund managers’ investment criteria and thus become less attractive for sell-side coverage. On this point, it is worth mentioning that part of it also comes from the restrictions imposed by MIFID II when it comes to research.

Exhibit 3

Source: EPRA Research - Bloomberg

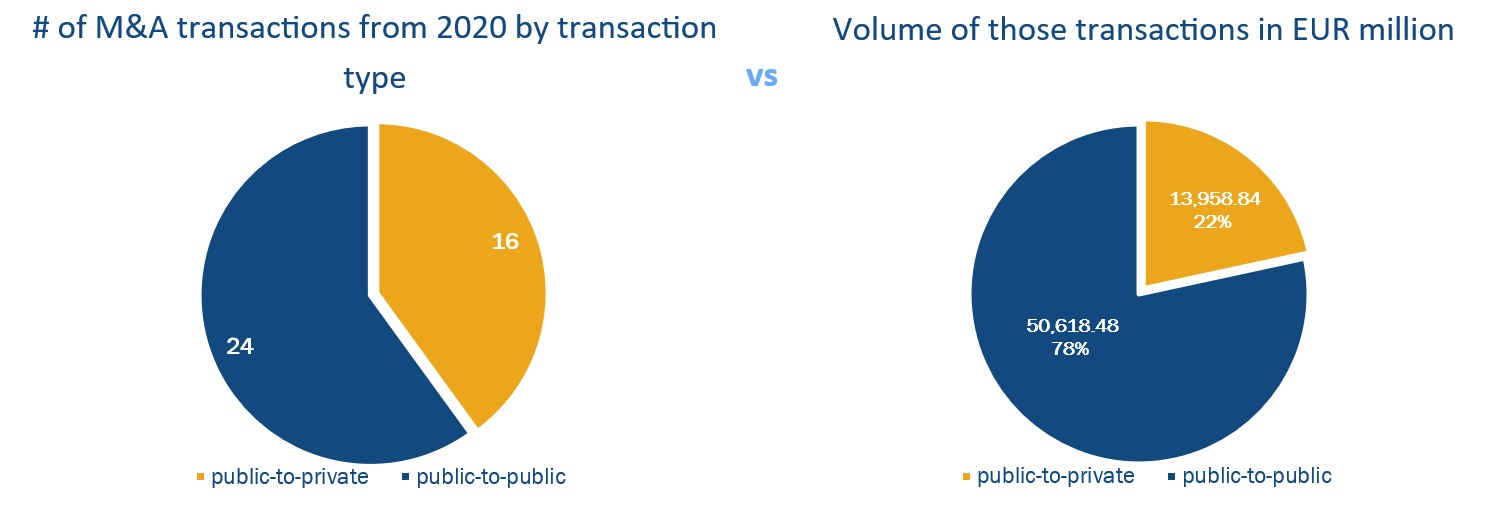

This lack of visibility may result in smaller companies falling into a dangerous loop, whereby limited access to capital constrains organic growth, which in turn could weaken investors’ appetite and perpetuate the cycle. These factors contribute to broader sector pressures, with the listed real estate sector currently trading at an average discount to NAV of approximately 28%[4], providing an enticing entry point for private equity firms to take over some of the most overlooked names in the index, but at the same time, creating opportunities for those companies to consider consolidation, enhancing scale and visibility. This is relevant because, although EPRA estimates that 16 out of 40 M&A transactions since 2020 have been private equity takeovers, public-to-public transactions have captured approximately 78% of the total transacted volume (ca. EUR 65 billion)[5], thereby creating larger investment vehicles with higher potential of accessing more capital and scale their operations.

Exhibit 4

Why does this matter? It matters because, today, around 60%[6] of the FTSE EPRA Nareit Developed Europe Index market capitalization sits within its twenty largest constituents. For active strategies, this creates an opportunity to gain exposure to the sector by focusing on more liquid names, avoiding the challenges associated with less-traded ones, though potentially missing out on opportunities to generate additional alpha by overlooking some great businesses. At the same time, flows into passive or quasi-passive investment vehicles naturally reinforce the upper end of the benchmark in line with current weights, strengthening the stability and liquidity of these larger companies.

To conclude, consolidation within the sector may present opportunities for smaller companies in the index to build stronger and more competitive vehicles, and at the same time, for larger ones, to leverage expanded operating platforms and enhanced economies of scale. This structural shift towards the upper end of the benchmark could lead the whole European listed real estate sector to increase its visibility and coverage compared to other equity sectors and, as a consequence, unlock access to a wider pool of institutional capital.